A headline in the Napa Register announces astronomical yields of cab and syrah this year. In part, it’s traceable to a cold front a few weeks ago that stalled the rise in brix levels and pushed “hang time” and harvest.

I suspect an updated census of the vines would also account for the bounty.

Before the Charles M. Schultz airport lost commercial flights (which coincided with economic shut-downs after 9/11), I’d get occasional birds-eye views of the surprisingly sweeping fields. With pride, I’d spot my little house, which seemed about to be swallowed by vineyards. I liked it that way. When I moved in, my street had 1 winery. I’d draw a star on the winery map practically adjacent to the star for the winery, write in my address, and send it to my family. Now, I count 7 stars including my address.

A few years ago, when the Gravenstein apple orchards along the highway named after them were ripped out and the apple processing plant shut down, West County mourned its heritage. We all sympathized with the workers and felt a sense of loss – as for the Cheese Shop’s croissant recipe I wished someone would have written down before the old baker died, or for the mislaid map my sister and I drew to mark the buried time capsule we left for the future. We knew the apples would never be replanted. But it became difficult to lament the rolling, vibrant fields bursting with chardonnay grapes each autumn. Just before Crush, a hold-out barn along Gravenstein Highway stacks tables with bushels of crunchy, tart apples, and signs appear in markets touting the “local” crop. They’re not ghosts, but the remaining orchards, wisely, keep themselves hidden.

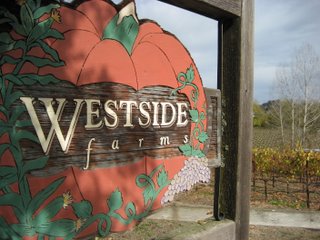

Eventually the traditional trek to Westside Farms for Halloween paraphernalia – field-plucked pumpkins, ornamental squash, popping corn crisped up on the spot – became increasingly complicated when they started charging for parking and required an army of teens to direct traffic. Then, one October, a lonely sign thanked passersby for loyal patronage. A vineyard came in the next spring.

Another summer, the scruffy blueberry farm that sent out annual “berries are here!” postcards so we wouldn’t miss its ultra-short harvest, sold its ancient bushes. The land, after all, proved ideal for a more opulent purple berry – pinot noir grapes.

I’d always felt content, before turning onto my street, passing an organic lettuce farm that sold only to specialty stores. Its 2 long greenhouses helped me spot my home from the air, and explaining it to out-of-town guests made me feel conscientious. For the first time this year, rootstock pokes up through yellow tubes.

They also sold the dirt lot just down the road with the grey-beige cows with floppy ears. I always felt a little sorry for them in their grass-free rectangle; in summers they’d crowd in the shade of a lone scraggly oak along the fence line, and in winter I’d see them standing steadfast in mud past their shins. Driving by the other day, I noticed a couple of burn piles, and the area seems to have been leveled. Instinct tells me that vines, on what must be a very fertilized acre or 2 of land, will soon thrive there.

The vineyards, my subdivisions, encroach. This sprawl of golden, green, and red every October beckons and the paparazzi come. We can’t escape the yeasty perfume of bulging, ripe grapes, nor can we deny their seduction. What new wine will we drink or hoard?

And when will we mind

what the vineyards erase?

The honey served an important medicinal role, too. A spoonful soothed a sore throat. More serious ailments called for a potion of honey and cloves, simmered with wine, rum, or cognac.

The honey served an important medicinal role, too. A spoonful soothed a sore throat. More serious ailments called for a potion of honey and cloves, simmered with wine, rum, or cognac.